Before The WNBA Tunnel, There Was The Glass Closet

with Guest Writer Tiana Randall

Welcome back to Tunnel Wars. Last episode, we had the WNBA player and coach, Ty Young on the podcast. Ty was was the #8 pick of the WNBA draft in 2008, and since then has seen the league drastically transform. Watch the episode here to see how her style evolved from “Tamera” to “Ty” as she found herself and the league loosened it’s dress code.

Tiana Randall, a style and beauty writer for Forbes Magazine gave us further insight into how players like Ty have broadened what the W can be.

xoxo,

Tunnel Wars

The tunnel was never supposed to be cool. Originally, it was just a passage, a strip of concrete meant for hauling goods, running utilities, or shuttling buses. But for athletes, it’s evolved into something closer to a pregame runway. In the NBA, the ritual really took off in the late ’90s, with one of the earliest moments being Michael Jordan in Paris, stepping off the bus in a beret and shuffling into a tunnel filled with reporters and paparazzi. Who’s to say that wasn’t the first tunnel fit?

What we do know is that it took another decade and a half before the tunnel became a real spectacle for women in the mid-to-late 2010s. Nobody was really documenting them in the tunnels or after games. For a long time, one of the only chances fans had to catch a glimpse of WNBA style was media day: the annual double-duty ritual where players not only faced the press but posed for those in-uniform team photos that would follow them all season, on posters, on TV, on trading cards, etc. It was either that or All-Star portraits or post-championship photos.

And while today’s media days double as a platform for players pinned photos on their Instagram grid, showing off their best fits and personalities, in the 2000s, they were anything but personal. Back then, the WNBA was still fresh, intent on projecting a marketable, “safe” image to win over future audiences. For many executives at the time, that allegedly meant one thing: being straight, or at least looking the part. In the 2022 documentary Dream On, which traced the making of the 1996 USA Women’s Basketball team and the birth of the WNBA, Rebecca Lobo recalled that, at the league’s genesis, players weren’t just “guinea pigs” for how the game would be played, they were experiments in how it would be sold. “We had to look and act a certain way,” she said. That way: being straight.

Sue Bird, former Seattle Storm guard, has been candid about this. Bird, who didn’t come out until she was 37, spent most of her career as the face of a league that didn’t fully embrace her whole self. “It was basically told to me that the only way I was going to have success from a marketing standpoint was to really sell this straight, girl-next-door image,” Bird says on the Pablo Torres Finds Out Podcast. “This is the way we’re going to sell the league, and, like, ‘Do you want to help the league grow?’” she was asked at just 21 years old. And at the time, it made sense. It was the early 2000s when being openly gay in sports, in general, carried a different weight.

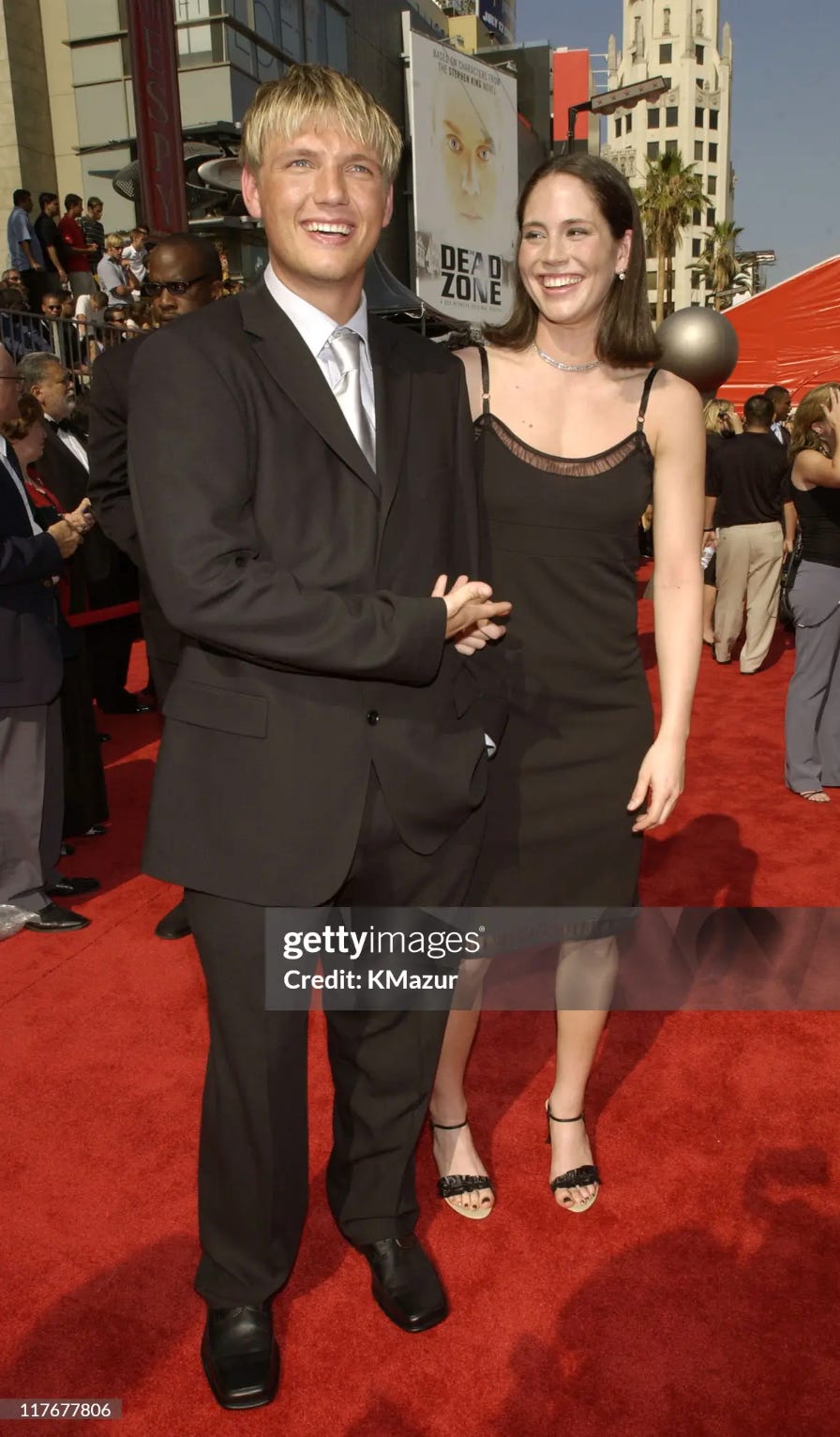

Now, the WNBA is abundant with players across the queer spectrum, where most players are either a stud or bud. It’s gotten to the point where being straight is a rarity, even jokingly dubbed “power straight” if you’re the only one on the team. But back then, Bird played along. She followed orders, posing for risqué shoots, attending premieres on the arms of men, and embodying that straight-girl-next-door fantasy plenty of teenage boys could hang on their bedroom walls.

Looking back at 2002 to 2011, “selling the league” often meant baring a lot of skin. The early to mid-aughts were all about halter tops, crop tops, plunging V and swoop-necks, asymmetrical cuts paired with short skirts, or that iconic crossed-neck halter slip dress — the look of a carefully crafted fantasy. But for players who were more masculine and openly gay — like Teresa Weatherspoon or Nicky McCrimmon — the uniform softened into white button-ups, unstructured suit jackets, corduroy pants, or velour track suits. The straight and gay codes were there, written in plain sight for anyone who wanted to see or was paying attention. Yet behind those outfits, for so many women, they were never seen or captured in the tunnel, but in the glass closet.

That same sentiment was spoken about in the new Diana Taurasi docuseries, Taurasi, on Prime. Journalist Kate Fagan says, “In the early days of the WNBA, they felt they had to capture the cookie-cutter audience they thought would bring in the bigger dollars and keep advertisers happy. Everybody had to be presented as straight, hyper-feminized, mainstream, quiet women.” And this was about Diana — slicked-back hair, sharp one-liners, buttoned-up shirt — Taurasi. Yet even Taurasi, one of the most unapologetic players the league has ever seen, fell in line.

It wasn’t about betraying herself so much as navigating an unwritten handbook rooted in a very specific idea of femininity, one designed to reassure corporate sponsors and traditional audiences that women’s basketball wouldn’t disrupt gender norms. For Taurasi, that meant showing up in halter tops, lipstick, and low-cut jeans, a curated version of herself that fit neatly into the league’s early branding strategy. The photos and outfit choices, although funny looking back on, are a reminder that in the WNBA’s formative years, style wasn’t a means for individualism, it was a form of compliance, a uniform stitched together as much for optics as for sport.

There were countless moments in WNBA history when executives and marketers undermined players’ true identities, but the move was always packaged as strategy, a way to build a league that could appeal to men, even if it meant eroding the very foundation they were laying. It was a contradiction baked into the league’s early DNA: sell authenticity, but only the kind that fit a predetermined mold. So when we revisit those old media day photos and see masculine-presenting lesbians dressed in sparkly tank tops and Y2K jeweled belts — it’s more than nostalgia. It’s proof that image-making in the WNBA often meant smoothing out the edges that made these players who they really were.

But the league, through the help of the players and fans, is making slow but big steps: implementing WNBA Pride nights and even poking light at the lesbian and queer domination of the league via multiple teams’ social media accounts. There are lesbian power couples from older generations like Sue Bird and Megan Rapinoe, and Diana Taurasi and Penny Taylor, who have been front and center of the women’s sports world. And the league is now even emphasizing its more masc’ players like the Natiesha Hiedman and Courtney Williams of Studbudz. Proving you can sell the league, without having to lose a part of yourself, something as core as your identity or sexuality.

The last line of this hits!